“Forward men, forward for God’s sake…”

“Forward men, forward for God’s sake…”

On the morning of July 1st, my wife, Victoria, and I got up early enough to enjoy breakfast at The Doubleday Inn with our housemates — a collection of congenial history buffs and their spouses.

On the morning of July 1st, my wife, Victoria, and I got up early enough to enjoy breakfast at The Doubleday Inn with our housemates — a collection of congenial history buffs and their spouses.

One of our fellow guests, a 40-something Pennsylvanian named John, was there by himself, and this was clearly not his first visit to Gettysburg. It was fun to see how enthused he was about getting out on the battlefield.

I shared John’s excitement as I downed my breakfast, a delicious, maple syrup drenched version of French toast that proved too heavy for Victoria. She needn’t have worried about the calories: battlefield tramping burns ‘em off big time.

I shared John’s excitement as I downed my breakfast, a delicious, maple syrup drenched version of French toast that proved too heavy for Victoria. She needn’t have worried about the calories: battlefield tramping burns ‘em off big time.

By the time we left the Doubleday Inn on Oak Ridge that morning, headed for the new Gettysburg Visitor Center and Museum, we could imagine General John Buford’s battle-weary cavalry corps falling back under fire from Confederate General Henry Heth’s reinforced infantry to positions along Oak Ridge (and the adjacent McPherson’s Ridge) 147 years ago.

Buford’s boys had been fighting off Heth’s two brigades since 5:00 AM, and here we were, two honeymooning sluggards, just getting into action at 9:00.

As we drove toward town and the Visitor Center, we could see the distinctive cupola of the Lutheran Seminary along Seminary Ridge, an important landmark on the battlefield in 1863 – and to this day. We could envision a grimly determined General Buford up in that cupola, field glasses in hand, watching the progress of the battle raging to his front, and looking anxiously to the rear for the approach of General Reynolds and his infantry corps.

As we drove toward town and the Visitor Center, we could see the distinctive cupola of the Lutheran Seminary along Seminary Ridge, an important landmark on the battlefield in 1863 – and to this day. We could envision a grimly determined General Buford up in that cupola, field glasses in hand, watching the progress of the battle raging to his front, and looking anxiously to the rear for the approach of General Reynolds and his infantry corps.

In fact, if we were there on that fateful morning in 1863, General Reynolds would soon be passing us on the road, riding up to the seminary and calling up to Buford, “How goes it, John?” Buford would reply, “The devil’s to pay!” and the next chapter of Gettysburg history would soon be written. But that would have to wait. We wanted to check out the new Visitor Center first.

In fact, if we were there on that fateful morning in 1863, General Reynolds would soon be passing us on the road, riding up to the seminary and calling up to Buford, “How goes it, John?” Buford would reply, “The devil’s to pay!” and the next chapter of Gettysburg history would soon be written. But that would have to wait. We wanted to check out the new Visitor Center first.

Our hosts at the Doubleday Inn (and several of our fellow guests) had spoken in glowing terms about the wonders of the new Museum and Visitor Center, which opened in April 2008 — and they were not blowing smoke. Victoria and I have been to a lot of National Park visitor centers, and this one blows them all away.

Our hosts at the Doubleday Inn (and several of our fellow guests) had spoken in glowing terms about the wonders of the new Museum and Visitor Center, which opened in April 2008 — and they were not blowing smoke. Victoria and I have been to a lot of National Park visitor centers, and this one blows them all away.

Far more than the usual place to pick up maps, brochures and a gift or two, the Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center is 22,000 square feet of exhibits, battlefield relics, inter-active exhibits, and multi-media presentations, including the film, “A New Birth of Freedom”, narrated by Morgan Freeman (who also starred in the film, Glory, which triggered my Civil War obsession in 1989).

Far more than the usual place to pick up maps, brochures and a gift or two, the Gettysburg Museum and Visitor Center is 22,000 square feet of exhibits, battlefield relics, inter-active exhibits, and multi-media presentations, including the film, “A New Birth of Freedom”, narrated by Morgan Freeman (who also starred in the film, Glory, which triggered my Civil War obsession in 1989).

Victoria and I watched the film and checked out the incredible exhibits – including the stretcher used to carry the mortally wounded Stonewall Jackson from the field at Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863. (Jackson’s death 8 days later would have dramatic repercussions at Gettysburg.)

The humble furnishings of Robert E. Lee’s personal field quarters were also on display, as were hundreds of period muskets, rifles, pistols, artillery shells, uniforms, and other treasures discovered on the battlefield over the years. It would be very easy to spend the entire day there – but with General Reynolds arriving on Seminary Ridge to reinforce Buford and the first day’s fighting heating up – we were eager to get back on the battlefield.

The humble furnishings of Robert E. Lee’s personal field quarters were also on display, as were hundreds of period muskets, rifles, pistols, artillery shells, uniforms, and other treasures discovered on the battlefield over the years. It would be very easy to spend the entire day there – but with General Reynolds arriving on Seminary Ridge to reinforce Buford and the first day’s fighting heating up – we were eager to get back on the battlefield.

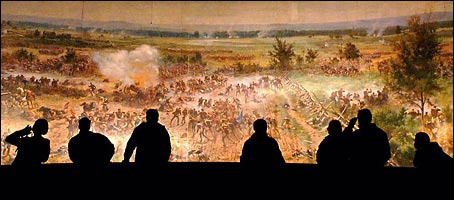

But first, we had to see the fully restored Gettysburg Cyclorama.

We’d seen it 20 years ago, when it was something of a sideshow attraction along with the old electronic map with its more than 600 lights that, for forty years, tracked the major action in the battle for visitors. Today, in its new home, the Gettysburg Cyclorama — the nation’s largest painting — gets its due.

We’d seen it 20 years ago, when it was something of a sideshow attraction along with the old electronic map with its more than 600 lights that, for forty years, tracked the major action in the battle for visitors. Today, in its new home, the Gettysburg Cyclorama — the nation’s largest painting — gets its due.

The massive artwork, entitled “The Battle of Gettysburg”, is a 360-degree cyclorama by the French artist Paul Dominique Philippoteaux. The vivid painting wraps around the curved walls of the exhibit, surrounding the viewer with a stunning, colorful, and violent depiction of “Pickett’s Charge” on July 3, 1863 – the climactic action of the three-days of unprecedented valor, fury and sacrifice that was The Battle of Gettysburg. You really have to see it to understand the scale and power of this thing. The whole experience made me proud to think “Your tax dollars at work.”

The massive artwork, entitled “The Battle of Gettysburg”, is a 360-degree cyclorama by the French artist Paul Dominique Philippoteaux. The vivid painting wraps around the curved walls of the exhibit, surrounding the viewer with a stunning, colorful, and violent depiction of “Pickett’s Charge” on July 3, 1863 – the climactic action of the three-days of unprecedented valor, fury and sacrifice that was The Battle of Gettysburg. You really have to see it to understand the scale and power of this thing. The whole experience made me proud to think “Your tax dollars at work.”

"Reynolds and the Iron Brigade" by Keith Rocco. © Keith Rocco and Traditional Studios http://www.keithrocco.com

After our rewarding morning at the Visitor Center, we drove back out to McPherson’s Ridge, where Heth’s reinforced Confederate brigades of General A.P. Hill’s corps were about to confront the vanguard of the Union Army of the Potomac, hurriedly deployed by its commander, General John Reynolds. Reynolds First Corps included the famous Iron Brigade, wearing their distinctive tall black hats. For Heth’s rebels, one look at “those damn black hats” made it clear that one of the Union’s hardest-fighting, battle-tested veteran infantry units had now joined the fight for the Gettysburg high ground.

After our rewarding morning at the Visitor Center, we drove back out to McPherson’s Ridge, where Heth’s reinforced Confederate brigades of General A.P. Hill’s corps were about to confront the vanguard of the Union Army of the Potomac, hurriedly deployed by its commander, General John Reynolds. Reynolds First Corps included the famous Iron Brigade, wearing their distinctive tall black hats. For Heth’s rebels, one look at “those damn black hats” made it clear that one of the Union’s hardest-fighting, battle-tested veteran infantry units had now joined the fight for the Gettysburg high ground.

Victoria and I knew that our first stop on McPherson’s Ridge would be a somber one: the spot where Reynolds fell, shot from his horse in the opening moments of the engagement as he urged his troops forward, bellowing, “Forward men, forward for God’s sake and drive those fellows out of those woods!”(Generals led from the front in those days.)

Victoria and I knew that our first stop on McPherson’s Ridge would be a somber one: the spot where Reynolds fell, shot from his horse in the opening moments of the engagement as he urged his troops forward, bellowing, “Forward men, forward for God’s sake and drive those fellows out of those woods!”(Generals led from the front in those days.)

The sudden loss of Reynolds was a brutal blow to the Union cause. John Reynolds wasn’t just any general – he was one of the Union army’s best.

Some historians maintain that Lincoln wanted to give Reynolds command of the Army of the Potomac, but that Reynolds demanded more autonomy than Lincoln could grant him. Ultimately, Lincoln put Pennsylvanian George Meade in charge of the Army of the Potomac with Reynolds leading the army’s First, Third, and Eleventh Corps.

Tributes left on July 1, 2010 at the spot where Reynolds fell include a poem someone wrote to honor him. Like the dog biscuits still left for Sallie the regimental mascot, these battlefield tokens always break my heart, yet also fill me with joy that, for some, history is a living thing.

Upon Reynold’s death, command of the Union forces fighting on McPherson’s Ridge and Oak Ridge devolved to General Abner Doubleday. (The Doubleday Inn, get it?) Two years earlier, Captain Doubleday had fired the first shot in defense of Fort Sumter, now, promoted to general, he was called upon to once again play a pivotal role in an epic moment.

Upon Reynold’s death, command of the Union forces fighting on McPherson’s Ridge and Oak Ridge devolved to General Abner Doubleday. (The Doubleday Inn, get it?) Two years earlier, Captain Doubleday had fired the first shot in defense of Fort Sumter, now, promoted to general, he was called upon to once again play a pivotal role in an epic moment.

And while it may well be that the claim Doubleday invented baseball in 1839 (he was in West Point at the time) is no more than a legend, what he did for the five furious hours after Reynolds death would have been legend enough for any man.

Doubleday’s men fought hard all morning, holding fast to the critical ridgelines just outside of town. As the Confederates threw wave upon wave of reinforcements into the fray, Doubleday’s 9,500 men battled ten Rebel brigades numbering more than 16,000, inflicting casualties on their attackers ranging from 35 to 50 percent in various regiments. The monuments that line McPherson’s Ridge and Oak Ridge are silent testaments to the valiant resistance of Doubleday’s troops in the face of overwhelming odds.

Eventually, Confederate troops finally pushed Doubleday off those ridgelines, past the Lutheran Seminary, and onto Cemetery Hill — where Union troops were concentrating to secure the high ground overlooking the town and fields below. At day’s end, Doubleday’s First Corps had lost two thirds of its men, dead, wounded, taken prisoner, or missing in action. But their sacrifice saved the day. The gallant stand made by Buford, Reynolds and Doubleday had kept the Confederates from reaching the high ground on Cemetery Hill.

The contest for that high ground – and victory on the bloody Gettysburg battlefield — would last two more days.

Victoria and I returned to The Doubleday Inn with a greater appreciation of the man whose name our pleasant B&B bore.

To be continued…