Produced, written, and performed by students, The Mee-Ow Show was established at Northwestern University in 1974, two years before my arrival on campus. In those two years, Mee-Ow underwent a swift transition from a wide-ranging, multi-media variety show to a sketch comedy show in The Second City tradition.

Produced, written, and performed by students, The Mee-Ow Show was established at Northwestern University in 1974, two years before my arrival on campus. In those two years, Mee-Ow underwent a swift transition from a wide-ranging, multi-media variety show to a sketch comedy show in The Second City tradition.

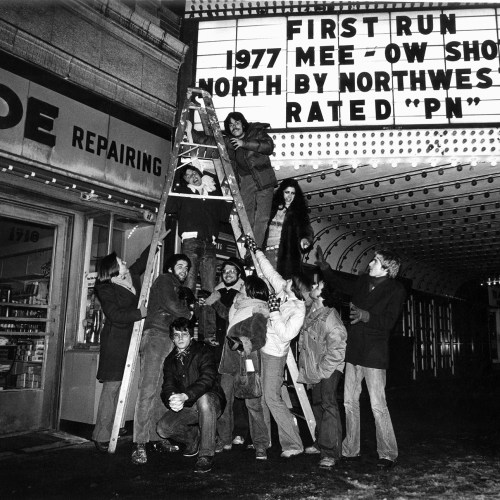

I went to McCormick Auditorium at Norris Center in the fall of my sophomore year to see the 1977 Mee-Ow Highlights Show: a collection of the best sketches from the previous two years’ worth of Mee-Ow revues, Spirit My Ass and North by Northwestern. Among the cast were Stew Figa, Jeff Lupetin, Betsy Fink, Suzie Plakson, Tom Virtue, Kyle Hefner, and Dana Olsen. It was the coolest, funniest live performance I’d seen since I hit campus.

Ass and North by Northwestern. Among the cast were Stew Figa, Jeff Lupetin, Betsy Fink, Suzie Plakson, Tom Virtue, Kyle Hefner, and Dana Olsen. It was the coolest, funniest live performance I’d seen since I hit campus.

The buzz at Norris Center’s McCormick Auditorium that night was electric — and response to the highlights show was wildly  enthusiastic. Mee-Ow was the hippest scene on campus – fast-eclipsing the popularity of The Waa-Mu Show: the traditional Northwestern student musical comedy revue first staged in 1929. Waa-Mu seemed crafted to entertain an older audience – something your parents could comfortably enjoy. But Mee-Ow felt more edgy, more subversive, made by-and-for the student body. It struck a resounding chord in me.

enthusiastic. Mee-Ow was the hippest scene on campus – fast-eclipsing the popularity of The Waa-Mu Show: the traditional Northwestern student musical comedy revue first staged in 1929. Waa-Mu seemed crafted to entertain an older audience – something your parents could comfortably enjoy. But Mee-Ow felt more edgy, more subversive, made by-and-for the student body. It struck a resounding chord in me.

Maybe the popularity of The Mee-Ow Show had something to do with the fact that it shared the fresh, irreverent spontaneity of NBC’s new late-night hit Saturday Night Live (then known as NBC’s Saturday Night) – which premiered in 1975, just a year after Mee-Ow made its debut. But I didn’t make that connection at the time because I wasn’t watching much TV. And I had yet to see a show at Second City.

All I knew was that these people, these fellow Northwestern students, were very funny. And polished. And cool. And I was wanted to be a part of that scene. So, I auditioned for the 1978 Mee-Ow Show, directed by North by Northwestern cast member, Kyle Heffner.

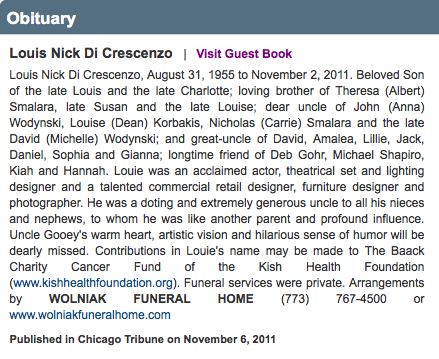

I arrived for the audition at the Norris Center student union and met an incoming sophomore, Rush Pearson. Rush, for some reason lost to memory, was walking with a cane — but we vibed right away. He was damned funny. Kinetic. Offbeat. And short like me. We were both full of what our parents would have called “piss and vinegar.” We didn’t know it then, but after the auditions were over and the cast was announced, Rush and I and a taller guy from the Chicago suburbs with one year of Mee-Ow under his belt, Dana Olsen, would form the core of the next three Mee-Ow Shows.

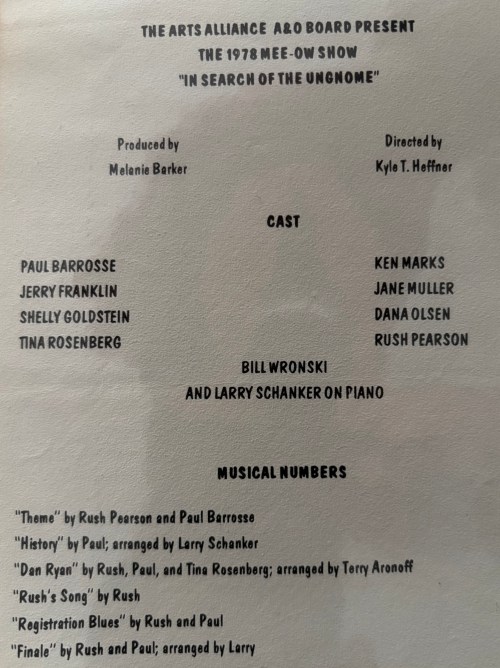

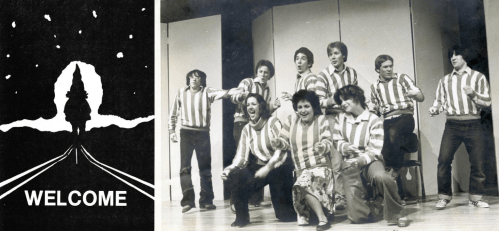

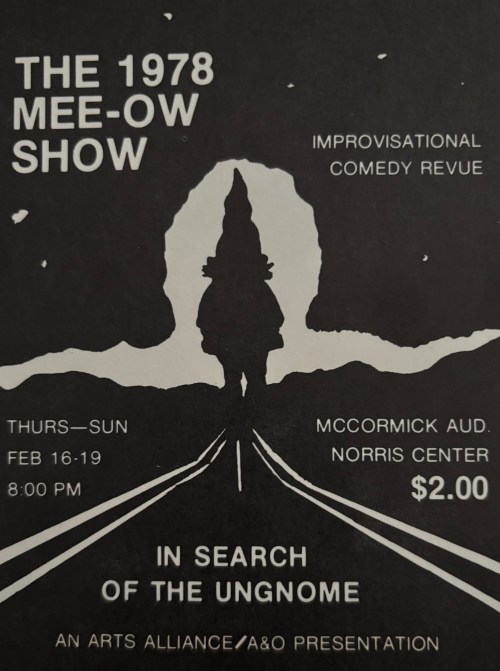

The 1978 Mee-Ow Show: “In Search of the Ungnome.”

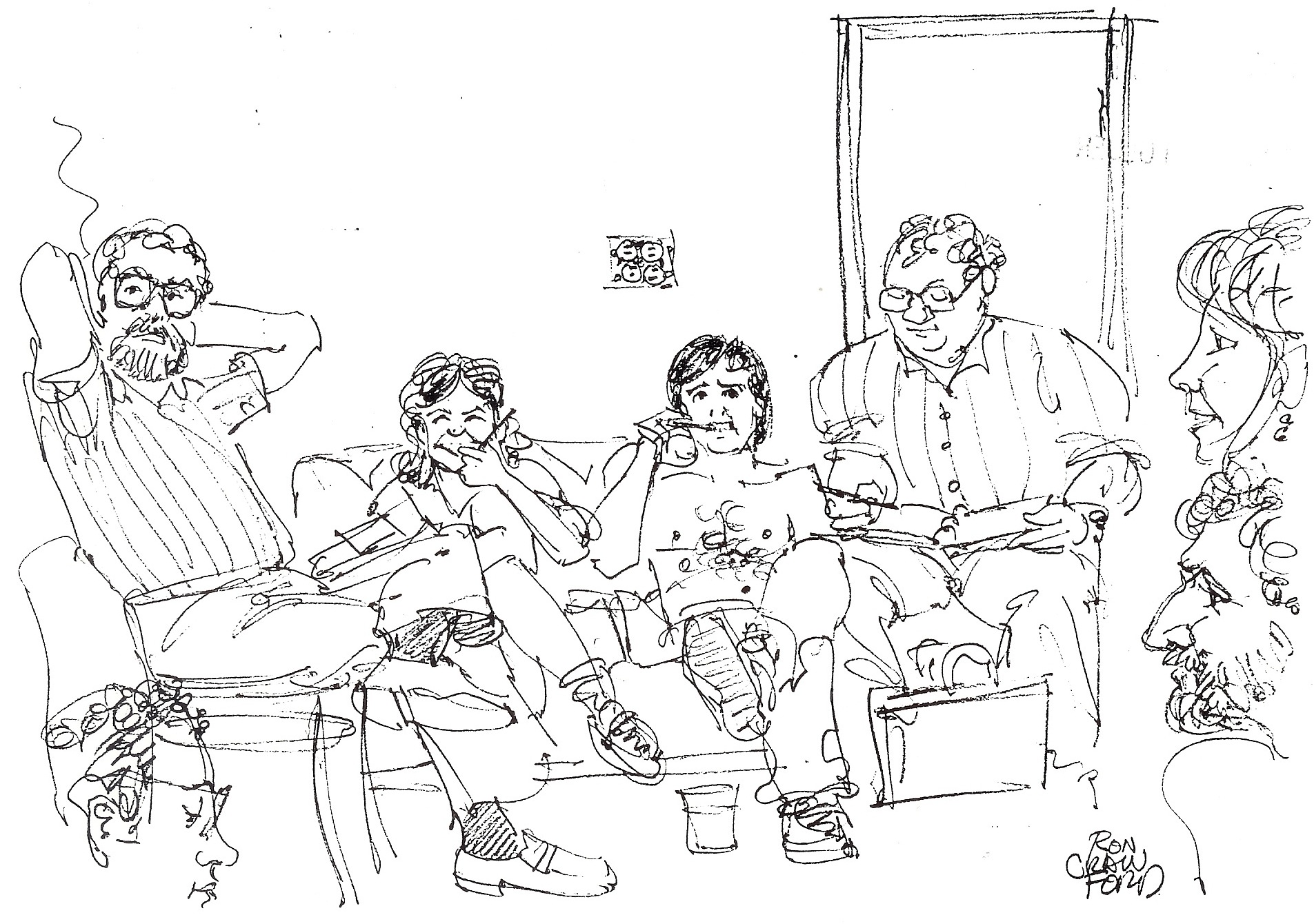

L to R: Jerry Franklin (hidden), Jane Muller, Dana Olsen, Shelly Goldstein, Bill Wronski, Ken Marks, Tina Rosenberg, Rush Pearson (obscured) & the author.

Directed by Kyle Heffner, the 1978 Mee-Ow Show was the very best thing about my sophomore year – and established the template for much of what I would do for the next decade – and beyond. Kyle set the standard for how an improvisational sketch revue should be created. We’d brainstorm comic premises, then improvise scenes based on those premises, record those improvisations – and then script our sketches based on what we recorded.

There was total freedom as we brainstormed the premises. No idea — no matter how absurd or esoteric or tasteless — was rejected out of hand. Then, Kyle would send us out of the room in groups for a few minutes to work out a rudimentary idea of how to structure a scene from one of these premises.

out of hand. Then, Kyle would send us out of the room in groups for a few minutes to work out a rudimentary idea of how to structure a scene from one of these premises.

In our groups, we’d hastily assign characters, devise a basic framework for the scene — and maybe even come up with a button to end it (which was rare). Then, we’d come back into the rehearsal room after ten minutes or so to improvise our scene for the rest of the cast and production crew. Those semi-structured improvisations were recorded and formed the basis for the first-draft scripts of each sketch – which would go through several revisions as we refined each sketch throughout the rehearsal process.

Sketches were living things: always growing, always progressing, getting tighter, more focused in their intent, more streamlined, leading up to a punchier, more trenchant, laughter/shock/surprise-inducing ending.

If a sketch doesn’t end well, then the next sketch starts from a deficit. It must win back the audience after an awkward moment — and that can kill a running order. That’s why, from those days forward, The Practical Theatre Company has never rested until we’ve done our best to satisfactorily “button” a sketch. (Alas, we don’t always succeed.)

If a sketch doesn’t end well, then the next sketch starts from a deficit. It must win back the audience after an awkward moment — and that can kill a running order. That’s why, from those days forward, The Practical Theatre Company has never rested until we’ve done our best to satisfactorily “button” a sketch. (Alas, we don’t always succeed.)

But let’s get back to 1978.

Improvisation is where it starts. And where it ends. But there’s lots of disciplined work between the beginning and end.

We’d commit our scripts to memory, so we had the confidence to overcome mistakes. In fact, reacting to mistakes was always an opportunity for a moment of unexpected, improvised fun with the audience. Confident in the through-line of the sketch and the final button, we could have some improvisational fun when the moment called for it.

opportunity for a moment of unexpected, improvised fun with the audience. Confident in the through-line of the sketch and the final button, we could have some improvisational fun when the moment called for it.

Kyle also had his Golden Rules. Knowing that too many improvisations ended with a knee-jerk reliance on violence and death, he declared that violence had to happen offstage. That edict, alone, would set our work apart from so many improv groups that would follow. Death and violence were no quick and easy way out.

Kyle also encouraged us to seek laughs above the belt – and not play to the lowest common denominator. Cursing and vulgarity were employed at a minimum. These were lessons I took to heart. And have tried to observe ever since.

That year, we were also blessed to have a genuine musical genius in our cast: piano virtuoso, Larry Schanker. Larry was just a freshman – but his talent was otherworldly. When Rush and I knocked out some chords and lyrics – Larry turned them into a Broadway anthem. And his pre-show overtures were worth the price of admission. Okay, so tickets were only two bucks. Larry’s talent made the show a hit before the cast came onstage. And he’s still doing it today.

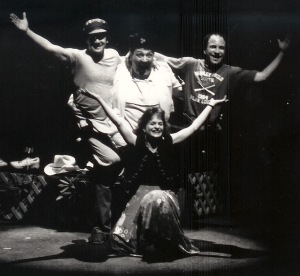

Rush and I shocked the crowd with a sketch called “Biafran Restaurant”. It was a moment in time. We were clad in our underwear, performing a sketch that juxtaposed a terrible African famine with a middle class American dining experience: balancing precariously on the comedic edge as we reminded the audience of an ongoing tragedy. These weren’t easy laughs. And it was glorious. We felt like we were pushing the envelope. And maybe we were. We were college sophomores – just starting to explore our comedic horizons.

Rush and I shocked the crowd with a sketch called “Biafran Restaurant”. It was a moment in time. We were clad in our underwear, performing a sketch that juxtaposed a terrible African famine with a middle class American dining experience: balancing precariously on the comedic edge as we reminded the audience of an ongoing tragedy. These weren’t easy laughs. And it was glorious. We felt like we were pushing the envelope. And maybe we were. We were college sophomores – just starting to explore our comedic horizons.

I loved everything about the Mee-Ow Show process: the music, the comedy, the late nights scripting sketches at Rush or Dana’s apartments after rehearsals. And when we performed the shows and the packed crowds laughed every night, I was hooked. I was home.

I loved everything about the Mee-Ow Show process: the music, the comedy, the late nights scripting sketches at Rush or Dana’s apartments after rehearsals. And when we performed the shows and the packed crowds laughed every night, I was hooked. I was home.

I wanted more. And luckily, I got it.